Cool Bugs VS Shitty Bugs, Part 1: Cool Bugs

Streaming video via Motion JPEG and counting established TCP sockets - a declarative promise with a catch

Recently I had to debug a problem in an Single Page Application (SPA) regarding Motion JPEG streams for one of my clients. I found this journey so interesting that I wanted to share it as my first blog post.

The post should give the reader an introduction on what it means to do frontend engineering nowadays. What follows is a post that touches on MJPEG streams, HTTP pushes, TCP sockets and their observability. What I assumed to be a bug in either the sent application or even the React library, just turned out to surprise me and I think it could surprise others as well.

So let’s step through it together and let me start by outlining the system of my client.

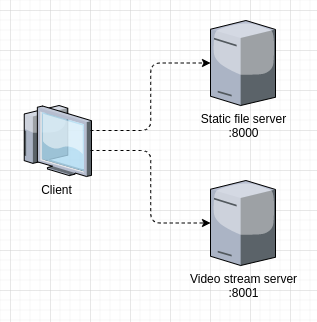

Describing the system

The system of my client contains, among other services, a statically served SPA (written with React) and a video stream server (written with ROS in C++/Python).

The stream server offers its data to the SPA in the Motion JPEG (MJPEG) format. MJPEG is an rather archaic approach, but still does its job well enough and hides all video interaction from the UI.

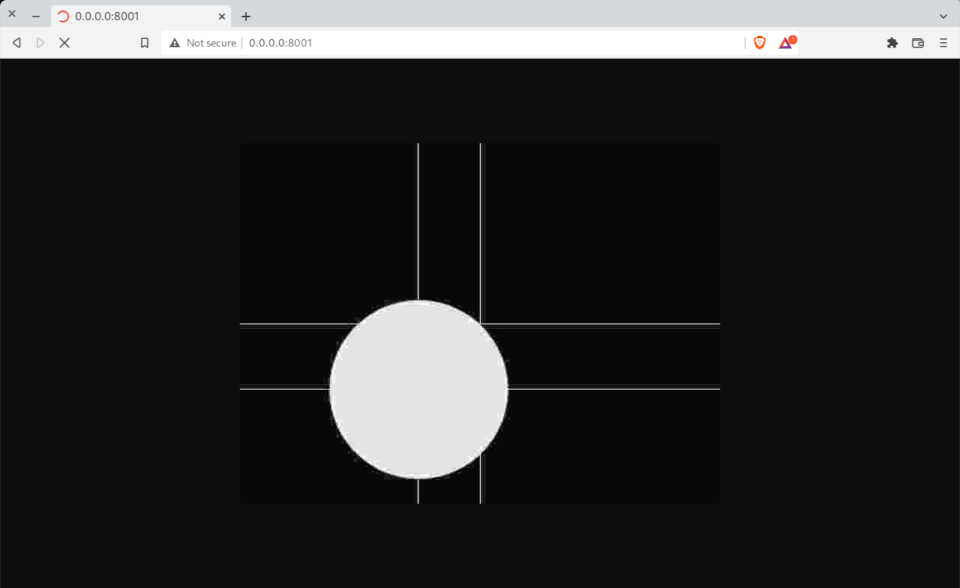

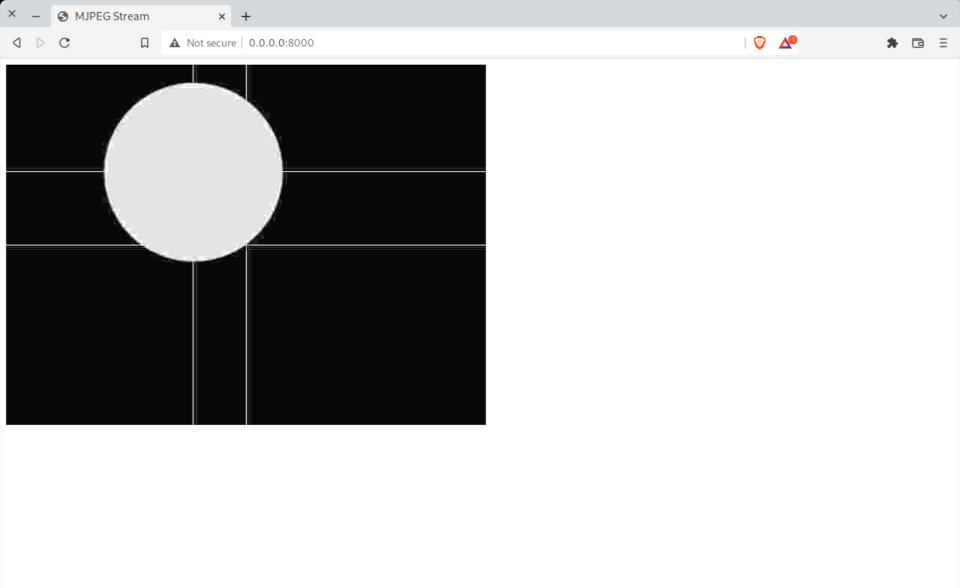

In the shipped product both servers run on different hosts, but for this post let’s assume the SPA is statically served via :8000 and the MJPEG server is serving its video stream via :8001, both on the same host 0.0.0.0.

The users are able to access the SPA via a Chromium-based browser and can then see the video stream in the center of the page. A responsive behavior is implemented as well, but apparently the system didn’t work as expected…

A bug in TODO

At the beginning of the week I found a new bug-ticket and its description contained something like the following:

By changing the size of the visible video stream in the UI more than 5 times, eg. by resizing the browser window, the video stream gets lost and the image just shows a blank background.

With the description being elaborate enough, I started up the two affected servers:

- the one serving the React SPA

- and the one MJPEG stream server

…and assumed that the video server got exhausted. I could imediately confirm my assumption as its logs contained entries like the following:

[mjpeg_server] WARN: too many open streams (6/5)

By resizing the browser window with the DevTools on the sidebar and by having the network tab open (with the filter set to Img, assuming Brave), I can observe that there are still data pushed from the MJPEG server; even though the stream got presumably “lost”. Even more interesting, all URIs that were ever used to request a MJPEG stream since session start were still receiving server pushes with streaming data from the server.

So it looks like each resize event that alters the URI for a new stream request doesn’t properly cleanup the streams that were previously requested. With each new such event the browser would just request another distinct stream from the MJPEG server and stack them up while keeping the older ones open.

Let’s have a look at the source code to get some insights and to compare the observed behavior with the current implementation.

Some of the systems current implementation

I just want to outline the concept here before I go on to create an isolated playground for the reader to try it out themselves.

React SPA

The React component for the stream viewer looked something like the following:

// stream.tsx

import * as React from "react";

export interface StreamProps {

/**

* visible height of the wrapping element in px

*/

height: number;

/**

* visible width of the wrapping element in px

*/

width: number;

}

export function Stream(props: StreamProps) {

/**

* choose between two possible streams based on the max visible size

*/

const resolution =

props.height >= 1080 && props.width >= 1920

? {

height: 1080,

width: 1920,

}

: {

height: 720,

width: 1280,

};

const src = `//0.0.0.0:8001/?resolution=${resolution.width}x${resolution.height}`;

return <img alt="loading stream..." src={src} {...props} />;

}

A simple stateless functional component in TypeScript that, depending on the available size, chooses a stream resolution to be either 1080p or 720p; adaptive streaming in a manual fashion, presumably to save some bandwidth and lower the computing resources on the MJPEG server. Its parent component did guarantee the aspect ratio and a proper handling of the resize event.

But, as I observed in the reproduction step above, even though the resize event causes a correct re-render of the Stream-component, the unmounted components were still receiving HTTP pushes from previously used streams. The stream just didn’t get released in the unmount cycle of the component, as I honestly would expect from this implementation and the declarative promise of React… so, a bug in React?

MJPEG Server

The MJPEG video stream server is implemented in C++ and for proprietary reasons I just want to outline the implemented behavior here with a short description. Later on I’ll provide some code, so we can create a MJPEG server the FOSS way.

Internally the streaming server gets its images by subscribing to a ROS Topic. It receives frames in a certain frequency, waits for a browser client to request a stream and then goes on with the encoding of a new MJPEG stream for each unique URI.

The browser client is in charge of some stream options via the query: resolution, framerate, quality etc. /?resolution=1920x1080 and /?resolution=1280x720 will produce two distinct MJPEG video streams with different resolutions, just as we’ve seen in the React Stream-component above. As present in the server logs, the maximum number of MJPEG streams is limited to 5 streams for a single server. Each client that requests a stream with an identical URI will consume the same MJPEG stream.

There are some comments in the source code mentioning:

Every created stream will be garbage collected after there is no application consuming it anymore and some timeout emitted after its last consumption.

To isolate the problem (and to provide some usable example code for the readers of this post) let me create an environment as vanilla as possible…

An isolated environment as playground

For reproducibility purposes I want to provide some simplified versions of the two mentioned servers. I need to create one server that provides an endless MJPEG video stream via HTTP and one that serves an simple SPA, so a request to the MJPEG stream can be done via the src attribute on an HTML img element.

tl;dr you can clone the mentioned files here.

A simple MJPEG server

The following packages are needed to launch the MJPEG server successfully (assuming Fedora):

The way MJPEG is streamed via HTTP is with the multipart/x-mixed-replace MIME type. I will cover the why’s and how’s later on when I go a bit into detail of the involved specs. But for now, let me just echo an HTTP MJPEG stream to STDOUT first.

I use gstreamer’s gst-launch cli to create a simple MJPEG media pipeline and, like in the Netscape example in the section below about specs, I prepend this load with some echoing for the initial multipart HTTP-header:

# start-stream.sh

#!/bin/bash

BOUNDARY_GST_PREFIX="--" # the gstreamer plugin seems to have a prefix for the boundary

BOUNDARY="-ThisRandomString---"

# multipart header

echo "HTTP/1.0 200"

echo "Content-type: multipart/x-mixed-replace;boundary=${BOUNDARY_GST_PREFIX}${BOUNDARY}"

echo ""

# multipart body parts

gst-launch-1.0 -q \

videotestsrc is-live=true pattern=ball motion=sweep ! \

videorate rate=0.04 ! \

video/x-raw,width=640,height=480,framerate=60/1 ! \

jpegenc quality=5 ! \

multipartmux boundary="${BOUNDARY}" ! \

filesink append=true location=/dev/stdout # the fdsink plugin didn't provide the needed `append` property to include the echoed header

I’m picking the sweeping ball test video source of gstreamer as my infinite stream here. Executing this script in the terminal will seemingly just output some gibberish (JPEG binary data), but inbetween you should be able to see that the necessary HTTP headers are in there as well.

A proper terminal output is ready now, so let me make use of netcat (nc) in listen mode to provide this output as an actual HTTP response from an server:

# serve.sh

#!/bin/bash

DIR=$( dirname "$( realpath "$0" )" )

nc -l -k -p 8001 -c "${DIR}/start-stream.sh"

So with a directory structure like the following:

.

├── serve.sh

└── start-stream.sh

0 directories, 2 files

…I can start my hacky MJPEG server with:

$ ./serve.sh

…to listen for HTTP requests on 0.0.0.0:8001 and respond with a MJPEG video stream.

Now to the SPA…

A simple vanilla SPA

For the SPA I also want to stay vanilla and try to work without any 3rd party library (eg. React):

<!-- index.html -->

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>MJPEG Stream</title>

<script src="/main.js"></script>

</head>

<body></body>

</html>

// main.js

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", () => {

main();

});

function main() {

// just a single mount-/unmount-cycle

addStream();

window.setTimeout(removeStream, 10000);

}

function addStream() {

const img = document.createElement("img");

img.setAttribute("id", "stream");

img.setAttribute("alt", "loading stream...");

img.setAttribute("src", "//0.0.0.0:8001/"); // ref to the netcat MJPEG server above

img.setAttribute("height", "480");

img.setAttribute("width", "640");

let count = 0;

img.addEventListener("load", () => {

console.log(`images loaded: ${++count}`);

});

document.body.appendChild(img);

}

function removeStream() {

const img = document.getElementById("stream");

if (!img) {

return;

}

img.remove();

}

Instead of removing the HTML element from the DOM through React with an resize event, I just use a timeout of 10s. This will provide - to my surprise - a setup that is already sufficient enough to recreate the observed bug, as I will now show.

I can serve those files with the static file server of my choice:

# serve.sh

#!/bin/bash

DIR=$( dirname "$( realpath "$0" )" )

python -m http.server --directory "${DIR}" 8000

…so with a directory structure like the following:

.

├── index.html

├── main.js

└── serve.sh

0 directories, 3 files

…I can start the SPA server with:

$ ./serve.sh

…and can consum the MJPEG stream with my vanilla SPA on 0.0.0.0:8000.

Let’s do some observations!

Observability

With the playground in place, let me observe the behavior of the loading MJPEG stream more closely.

Playing on the playground

The browser already gives me quite some information on the network activity, even before consulting additional tools. With a visit on 0.0.0.0:8000 it lets me observe the following things.

On Brave:

- the images of the stream get properly rendered without stutter for 10s

- the logs contain a single entry:

images loaded: 1 - the stream keeps loading in the background after the HTML

imgelement has been removed from the DOM

On Firefox (just for completeness):

- no image of the stream is shown (just an occasional single frame on my system, if I’m even lucky)

- there are quite some log entries á la

images loaded: x, seemingly for each multipart body part - the stream also keeps loading in the background after the HTML

imgelement has been removed from the DOM (and it even keeps logging entries!)

My client just focusses on Chromium based browsers with their product, but UH OH! this difference in modern browser engines is worrysome. Why does the browser keep receiving data after the img HTML element has been removed from the DOM in both cases?

Let me observe the established TCP sockets for the MJPEG server on OS level.

Making established TCP sockets visible

After feeling enlightened and motivated by Brendan Gregg’s books BPF Performance Tools: Linux System and Application Observability and Systems Performance: Enterprise and the Cloud, let me get a list of all the established TCP sockets, from the browser (source) to the MJPEG server (destination).

With both servers running on my machine (with the scripts above) I can observe the established sockets for my destination with ss.

$ ss -HOna4t state established '( dst = 127.0.0.1:8001 )'

0 0 127.0.0.1:59590 127.0.0.1:8001

To observe any changes more easily I can watch the output of the command also continuously as frequent as every 100ms.

$ watch -n 0.1 "ss -HOna4t state established '( dst = 127.0.0.1:8001 )'"

Every 0.1s: ss -HOna4t ... dell-precision-5560.localdomain: Fri Apr 1 21:28:12 2022

0 0 127.0.0.1:59590 127.0.0.1:8001

If you don’t have ss available on your system (maybe on MacOS?), netstat and awk provide similar capabilities.

$ watch -n 0.1 "netstat -4nt | awk '"'{ if ($5 == "127.0.0.1:8001" && $6 == "ESTABLISHED") print $0 }'"'"

Every 0.1s: netstat -4n... dell-precision-5560.localdomain: Fri Apr 1 21:29:28 2022

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:59592 127.0.0.1:8001 ESTABLISHED

If I’m only interested in the number of established sockets, I could narrow it down even further to a single numeric value. With one line per socket I could just count the number of lines.

$ watch -n 0.1 "ss -HOna4t state established '( dst = 127.0.0.1:8001 )' | wc -l"

…or with netstat / awk:

$ watch -n 0.1 "netstat -4nt | awk '"'{ if ($5 == "127.0.0.1:8001" && $6 == "ESTABLISHED") print $0 }'"' | wc -l"

With one of those observability one-lines running in the terminal I now have the visible indicator on OS level. I can clearly see that the established TCP socket doesn’t get closed after the HTML img element has been removed from the DOM.

We knew that one before by deriving that info from the network tab in the DevTools, but making it scriptable in the terminal could give us some idea on how to test this behavior in an browser-independent, automated way.

Let me have a look at the specs. Maybe this behavior is expected or maybe they could give me another hint…

Gathering some insights on some involved specs

Let’s step from lowest to highest level: TCP sockets, MJPEG streaming via HTTP pushes, and the DOM elements.

TCP / RFC 793

Did you ever had a look at the TCP RFC?

What interests me in this case is the section about the different states that a TCP socket can have:

A connection progresses through a series of states during its

lifetime. The states are: LISTEN, SYN-SENT, SYN-RECEIVED,

ESTABLISHED, FIN-WAIT-1, FIN-WAIT-2, CLOSE-WAIT, CLOSING, LAST-ACK,

TIME-WAIT, and the fictional state CLOSED. CLOSED is fictional

because it represents the state when there is no TCB, and therefore,

no connection. Briefly the meanings of the states are:

LISTEN - represents waiting for a connection request from any remote

TCP and port.

SYN-SENT - represents waiting for a matching connection request

after having sent a connection request.

SYN-RECEIVED - represents waiting for a confirming connection

request acknowledgment after having both received and sent a

connection request.

ESTABLISHED - represents an open connection, data received can be

delivered to the user. The normal state for the data transfer phase

of the connection.

FIN-WAIT-1 - represents waiting for a connection termination request

from the remote TCP, or an acknowledgment of the connection

termination request previously sent.

FIN-WAIT-2 - represents waiting for a connection termination request

from the remote TCP.

CLOSE-WAIT - represents waiting for a connection termination request

from the local user.

CLOSING - represents waiting for a connection termination request

acknowledgment from the remote TCP.

LAST-ACK - represents waiting for an acknowledgment of the

connection termination request previously sent to the remote TCP

(which includes an acknowledgment of its connection termination

request).

TIME-WAIT - represents waiting for enough time to pass to be sure

the remote TCP received the acknowledgment of its connection

termination request.

CLOSED - represents no connection state at all.

A TCP connection progresses from one state to another in response to

events. The events are the user calls, OPEN, SEND, RECEIVE, CLOSE,

ABORT, and STATUS; the incoming segments, particularly those

containing the SYN, ACK, RST and FIN flags; and timeouts.

The state diagram in figure 6 illustrates only state changes, together

with the causing events and resulting actions, but addresses neither

error conditions nor actions which are not connected with state

changes. In a later section, more detail is offered with respect to

the reaction of the TCP to events.

NOTE BENE: this diagram is only a summary and must not be taken as

the total specification.

+---------+ ---------\ active OPEN

| CLOSED | \ -----------

+---------+<---------\ \ create TCB

| ^ \ \ snd SYN

passive OPEN | | CLOSE \ \

------------ | | ---------- \ \

create TCB | | delete TCB \ \

V | \ \

+---------+ CLOSE | \

| LISTEN | ---------- | |

+---------+ delete TCB | |

rcv SYN | | SEND | |

----------- | | ------- | V

+---------+ snd SYN,ACK / \ snd SYN +---------+

| |<----------------- ------------------>| |

| SYN | rcv SYN | SYN |

| RCVD |<-----------------------------------------------| SENT |

| | snd ACK | |

| |------------------ -------------------| |

+---------+ rcv ACK of SYN \ / rcv SYN,ACK +---------+

| -------------- | | -----------

| x | | snd ACK

| V V

| CLOSE +---------+

| ------- | ESTAB |

| snd FIN +---------+

| CLOSE | | rcv FIN

V ------- | | -------

+---------+ snd FIN / \ snd ACK +---------+

| FIN |<----------------- ------------------>| CLOSE |

| WAIT-1 |------------------ | WAIT |

+---------+ rcv FIN \ +---------+

| rcv ACK of FIN ------- | CLOSE |

| -------------- snd ACK | ------- |

V x V snd FIN V

+---------+ +---------+ +---------+

|FINWAIT-2| | CLOSING | | LAST-ACK|

+---------+ +---------+ +---------+

| rcv ACK of FIN | rcv ACK of FIN |

| rcv FIN -------------- | Timeout=2MSL -------------- |

| ------- x V ------------ x V

\ snd ACK +---------+delete TCB +---------+

------------------------>|TIME WAIT|------------------>| CLOSED |

+---------+ +---------+

TCP Connection State Diagram

Figure 6.

Data can flow on an ESTABLISHED state, that’s why I added an additional filter to the observability one-liners.

So an HTML img element, with the TCP remote set in the src attribute, creates and keeps an ESTABLISHED TCP socket, even after the HTML element has been removed from the DOM. But why doesn’t the browser close the socket to the MJPEG server?

Video streaming via Motion JPEG

Streaming MJPEG is rather simple, as I already showed in the playground script above. I could find that information spread out on multiple sources. (I think the following specs are interesting, but feel free to skim those if you’re not into specs that much.)

Wikipedia has a nice overview:

In response to a GET request for a MJPEG file or stream, the server streams the sequence of JPEG frames over HTTP. A special mime-type content type multipart/x-mixed-replace;boundary=<boundary-name> informs the client to expect several parts (frames) as an answer delimited by <boundary-name>. This boundary name is expressly disclosed within the MIME-type declaration itself. The TCP connection is not closed as long as the client wants to receive new frames and the server wants to provide new frames. […]

The specific MIME type in the content type of the HTTP response (that enables the server to push a stream to the client) originates from this post on Server Pushes from Netscape back in the day:

For server push we use a variant of “multipart/mixed” called “multipart/x-mixed-replace”. The “x-” indicates this type is experimental. The “replace” indicates that each new data block will cause the previous data block to be replaced – that is, new data will be displayed instead of (not in addition to) old data.

So here’s an example of “multipart/x-mixed-replace” in action:

Content-type: multipart/x-mixed-replace;boundary=ThisRandomString

--ThisRandomString

Content-type: text/plain

Data for the first object.

--ThisRandomString

Content-type: text/plain

Data for the second and last object.

--ThisRandomString--

[…]

So here’s exactly what happens:

- Following in the tradition of the standard “multipart/mixed”, “multipart/x-mixed-replace” messages are composed using a unique boundary line that separates each data object. Each data object has its own headers, allowing for an object-specific content type and other information to be specified.

- The specific behavior of “multipart/x-mixed-replace” is that each new data object replaces the previous data object. The browser gets rid of the first data object and instead displays the second data object.

- A “multipart/x-mixed-replace” message doesn’t have to end! That is, the server can just keep the connection open forever and send down as many new data objects as it wants. The process will then terminate if the user is no longer displaying that data stream in a browser window or if the browser severs the connection (e.g. the user presses the “Stop” button). We expect this will be the typical way people will use server push.

- The previous document will be cleared and the browser will begin displaying the next document when the “Content-type” header is found, or at the end of the headers otherwise, for a new data block.

- The current data block (document) is considered finished when the next message boundary is found.

- Together, the above two items mean that the server should push down the pipe: a set of headers (most likely including “Content-type”), the data itself, and a separator (message boundary). When the browser sees the separator, it knows to sit still and wait indefinitely for the next data block to arrive.

Putting it all together, here’s a Unix shell script that will cause the browser to display a new listing of processes running on a server every 5 seconds:

#!/bin/sh

echo "HTTP/1.0 200"

echo "Content-type: multipart/x-mixed-replace;boundary=---ThisRandomString---"

echo ""

echo "---ThisRandomString---"

while true

do

echo "Content-type: text/html"

echo ""

echo "<h2>Processes on this machine updated every 5 seconds</h2>"

echo "time: "

date

echo "<p>"

echo "<plaintext>"

ps -el

echo "---ThisRandomString---"

sleep 5

done

So much to the historic Netscape post.

The following is an excerpt from the HTML specs by the WHATWG on multipart/x-mixed-replace:

For the purposes of algorithms processing these body parts as if they were complete stand-alone resources, the user agent must act as if there were no more bytes for those resources whenever the boundary following the body part is reached.

Thus, load events (and for that matter unload events) do fire for each body part loaded.

Can you notice the bit about the load events: “load events […] do fire for each body part loaded.”? It seems that each received MJPEG frame should emit the load event… Brave only emits the one for the first frame, but Firefox seemingly does emit on all frames!

Here are the relevant bits of the “process a navigate response"-section from the HTML spec:

To process a navigate response, given a string navigationType, a boolean allowedToDownload, a boolean hasTransientActivation, and a navigation params navigationParams:

Let response be navigationParams's response. Let browsingContext be navigationParams's browsing context. Let failure be false. If response is a network error, then set failure to true. Otherwise, if the result of Should navigation response to navigation request of type in target be blocked by Content Security Policy? given navigationParams's request, response, navigationParams's policy container's CSP list, navigationType, and browsingContext is "Blocked", then set failure to true. [CSP] Otherwise, if navigationParams's reserved environment is non-null and the result of checking a navigation response's adherence to its embedder policy given response, browsingContext, and navigationParams's policy container's embedder policy is false, then set failure to true. Otherwise, if the result of checking a navigation response's adherence to `X-Frame-Options` given response, browsingContext, and navigationParams's origin is false, then set failure to true. If failure is true, then: [...] Return. This is where the network errors defined and propagated by Fetch, such as DNS or TLS errors, end up being displayed to users. [FETCH] If response's status is 204 or 205, then return. If response has a `Content-Disposition` header specifying the attachment disposition type, then: [...] Return. Let type be the computed type of response. If the user agent has been configured to process resources of the given type using some mechanism other than rendering the content in a browsing context, then skip this step. Otherwise, if the type is one of the following types, jump to the appropriate entry in the following list, and process response as described there: [...] "multipart/x-mixed-replace" Follow the steps given in the multipart/x-mixed-replace section providing navigationParams. Once the steps have completed, return. [...]

Oki, so much for MJPEG streaming. The server is in charge of the framerate and both (server and client) can terminate the connection. Let’s have a look at the spec for the HTML img element.

HTMLImageElement

Obvious sources are the HTML spec by the WHATWG and the elaborating notes on MDN.

I guessed what could be of interest for my bug is the complete attribute. This bit on MDN in particular caught my attention:

Returns a boolean value that is true if the browser has finished fetching the image, whether successful or not. That means this value is also true if the image has no src value indicating an image to load.

Here is even more detail about the use of the complete-attribute:

The image is considered completely loaded if any of the following are true:

- Neither the src nor the srcset attribute is specified.

- The srcset attribute is absent and the src attribute, while specified, is the empty string (”").

- The image resource has been fully fetched and has been queued for rendering/compositing.

- The image element has previously determined that the image is fully available and ready for use.

- The image is “broken;” that is, the image failed to load due to an error or because image loading is disabled.

The part about "[…] is also true if the image has no src value […]" and “The image is considered completely loaded if […] Neither the src nor the srcset attribute is specified.” lead me to the assumption that if I remove the src attribute from the HTML element, then the browser might consider the load of the image as being completed and will properly close the established TCP socket.

So let me just try to remove the src attribute before I remove the element from the DOM!

I hope we’ll learn something new here…

So right before the call to img.remove() in the vanilla SPA, I include a call to remove the src attribute.

// ...same as above

function removeImage() {

const img = document.getElementById("stream");

if (!img) {

return;

}

// without the removal of the `src` attribute, the stream will continue

// loading data in the background

img.removeAttribute("src");

img.remove();

}

Now, when I observe the established sockets with the little hacky watcher again:

$ watch -n 0.1 "ss -HOna4t state established '( dst = 127.0.0.1:8001 )'"

…I can see that the established TCP socket gets closed properly.

Wow! What was missing is a surprising client-side img.removeAttribute("src") right before the call to img.remove(), otherwise the socket will stay open and continue to receive pushes from the MJPEG server. (As a friend later pointed out I was not alone with my assumption.)

So in the React SPA of my client I archieve the same behavior by using an effect hook. That one should remove the attribute in the unmount cycle:

import * as React from "react";

export interface StreamProps {

// ...same as above

}

export function Stream(props: StreamProps) {

// ...same as above

const src = `//0.0.0.0:8001/?resolution=${resolution.width}x${resolution.height}`;

/**

* use a ref to manage the 'src' attribute in a manual fashion

*

* NOTE: if we don't manage the src attribute manually then the TCP socket will

* keep an established connection to the MJPEG server and receive the stream

* until it gets exhausted

*/

const imgRef = React.useRef<React.HTMLImageElement>(null);

React.useEffect(() => {

const img = imgRef.current; // keep the ref to use it in the unmounting cycle

if (img) {

img.setAttribute("src", src);

}

return () => {

if (img) {

img.removeAttribute("src");

}

};

}, [src]);

/**

* ...and replace the `src` attribute with a `ref`

*/

return <img alt="loading stream..." ref={imgRef} {...props} />;

}

…and just like that I only stream the data for the video that is also present in the DOM. Finally the MJPEG server can properly garbage collect its unused streams!

Going further, I included some additional conditions to handle even smaller resolutions than 720p to save even more resources.

Conclusion

In this post I reproduced the bug properly, elaborated the process on how to isolate the problem and got to write some useful scripts that provide observability of established TCP sockets. I think it’s nice to see that modern frontend engineering involves quite some knowledge about a working system, the complexity of browsers and sometimes a thorough read through specs and historical references. What’s missing might be a look into the Chromium source code.

There seems to be an interesting quirk with an Image being loaded via multipart-HTTP-pushes in an responsive implementation. In the end I just assume that an Image doesn’t get garbage collected by the browser engine after the removal from the DOM, as it’s expected to complete the loading of the resource first. Maybe this behavior clashes with multipart-HTTP-pushes, especially together with the behavior of the load event as that one doesn’t even seem to be according to spec. The declarative promise of React just distorted my perspective regarding source fetching here, but I also think it shouldn’t make an effort to provide a declarative solution.

Regarding responsive images, I did also try out the srcset attribute for multi-source fetching without any scripting, but that one had even more quirks, since the image with the higher quality was (once loaded) always the preferred one. I might cover this in a followup post and wonder if there are other HTML elements that suffer from such surprises like the HTMLImageElement?

…and, what was so cool about the bug?

A cool bug is so complex that it becomes hard to avoid during development, even after making every decision reasonably well. Such a bug is deeply hidden in some spec, maybe even just an implicit behavior and can’t be easily looked up in any documentation of a library. I could have easily created such a bug myself and solving it makes me feel like I could grow as a software engineer simply by fixing it. Unfortunately, cool bugs are rare!

Here’s a quick list of all the awesome tools that were touched in this journey:

netcat(nc)gstreamer(gst-launch)ss(ornetstat/awkfor MacOS)

Thank you for having a look and stepping through it with me!

And thank you, Mihail Georgescu & Dominik Manser, for feedback and proof reading this blog post!